Maraong manaóuwi.

Gadigal for ‘emu footprints’.

These footprints form the welcome mat laid before visitors to Hyde Park Barracks.

For Gadigal elder, Uncle Allen Madden, they mark the imprint of the first native animal to disappear from Sydney, after many thousands of years of calling this area home.

In the eyes of those more familiar with the shorter version of our city’s past, they might represent a memory of Sydney’s convict story.

For Jonathan Jones, the Wiradjuri/Gamilaroi artist responsible for creating them, they are both.

Walking through the entry to Hyde Park Barracks, Jones’ installation seems so ‘at home’ that it isn’t apparent at first that the striking motif stretching underfoot across the full length and span of the courtyard is a new feature here, albeit surrounding one of Sydney’s oldest buildings.

Hyde Park Barracks reopened today after extensive redevelopment as one of Sydney’s Living Museums.

I timed my visit to coincide with a traditional clearing dance from Lucy and Lowanna Murray, two young Wiradjuri women from Cowra (where the stones for Jones’ artwork were sourced) and the official Welcome to Country from Uncle Allen, ceremonially opening the barracks to the public.

Jones and Uncle Allen talked about the importance of the site, for both indigenous and colonial Australia. There was a lot to learn about the sandstone crafted into these buildings, as well as the role of art in communicating the Aboriginal experience and story.

Jonathan explained his use of the emu as the motif for his artwork. Emu is looked to as a template for the role men should play in society. The only native animal where the father cares for the egg, emu is a role model for fatherhood in Aboriginal culture.

Uncle Allen spoke about the importance of taking time to look around and notice the land around us, rather than witnessing the world through our iPhone screens.

You have to take the time to look around you. Why look at it in a museum, in a picture frame, when you could look at it right in front of you?

Uncle Allen Madden

It was fitting advice as I donned the audio guide headphones which accompanied me through each room with voiceovers determined by geolocation technology.

It’s an immersive experience, surrounded by the sounds of the barracks with stories and details of convict, immigrant and indigenous life in the earliest days of Sydney’s development.

Growing up in Sydney, these stories don’t seem particularly new. On the surface.

What has impact is the layering of new detail on the history of this city that adds meaning and explains so much about Sydney…

… that it was the navigation routes and walking trails of the First Nations people on which the colony’s earliest roads were based, at the same time an acknowledgement of the knowledge of the original owners of the land and a paving over and erasing of thousands of years of history.

… how a lack of understanding of the concept of collective responsibility for the land, rather than ownership of it, resulted in such bloody disagreement and massacre.

… that the very isolation of this place meant that simply being in Sydney was the prison sentence, so convicts experienced days and days of ‘freedom’ away from watchful eyes while sent off to, say, source timber for building.

It’s these layers of story and history that make exploring Hyde Park Barracks so arresting. Uncle Allen spoke of the importance of preserving and protecting language and culture, keeping it alive through story and art.

We have a responsibility for the language of the country that we live on: to look after that.

Uncle Allen Madden

The new Hyde Park Barracks Experience is also keeping our stories alive, bringing life to the story of my city and its people, old and ancient. It is well worth a visit.

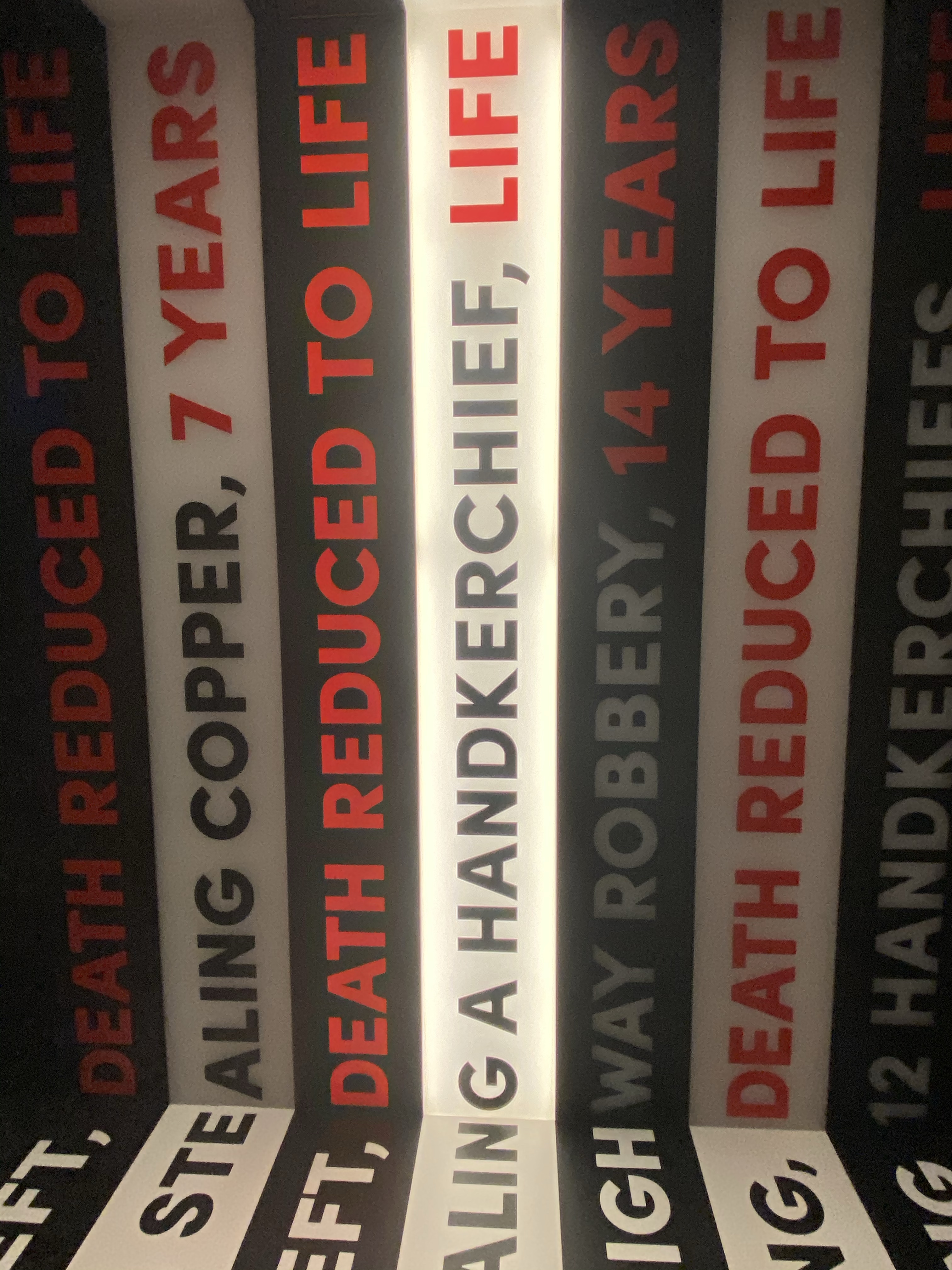

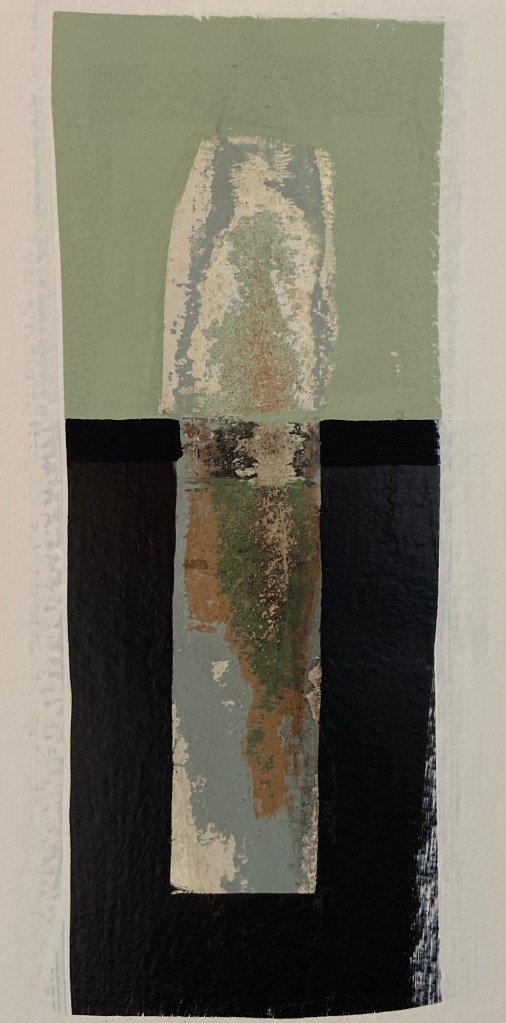

Photo of the Day: